What might Marcel Duchamp have been thinking about as he sat in his apartment on Munich’s Barerstrasse and speculated about how he could explode painting? Duchamp wanted to revolutionise “oilfactory masturbation”, as he later described the art world’s fixation on oil and canvas, and to invent other forms of expression.The fact that this occurred nearly simultaneously with the revolution of abstract form that the painters of the Blue Rider introduced in the same city – in a street that half a century later would also serve Rainer Werner Fassbinder as the backdrop for his first feature film, Katzelmacher – draws our attention away from the autonomous work of art and towards the psychological functions of urban space.What role does such urban space play in the psychology of decisionmaking processes? Public space as an urban map teaches us nothing about the barely visible nexus of sequences of events, borders, structures and exchanges of all kinds or about the intense experiences that follow from all these things. Neither the materiality nor the monumentality of architectures presents a challenge to visual artists who have decided to leave the white cube; rather, it is the systems of signs, the channels of communications and the places for collecting and meeting. Influencing the quotidian ritual, encouraging the pulsing vitality and making its automatisms visible will all succeed better if one knows the context of the urban matrix that structures the locations.

The visual language that Szuper Gallery have been using for several years to gut these automatisms is that of absurdity. Derived from Beckettian performances, it is presented in the form of media performances in which the actors and camera look each other in the eye, forming a closed system. For the décor of their performances, they often seek out imposing buildings.The central office of the financial news service company Bloomberg Media or that of the city planning office of the state capital Munich.The members of the collective Szuper Gallery scratch away at the symbolic value of this institutional landscape and at the gleaming surface of the “corporate image strategy” of the financial world. A subversive, anarchistic, absurd humour is brought to bear in their self-presentations in photographic and video works.Whether it is the bizarre sexuality of the green uniforms of motorcycle police officers or the dysfunctional “after-hours” activities in the control centre of the financial world of the Bloomberg financial data company or the downwards sailing of red cloth in the administration building of the urban planning office, their interventions introduce uncontrollable, absurd choreographies into the organisation, efficiency and logic of power.Their fictive allusions to the ambitions of artists, success and high prices – which the name Szuper Gallery seems to promise – stand in contradiction to the fact that they are always in the wrong place, as genius amateurs in a professional, efficient ambiance of super modernity.A few years ago I wrote about these works:“no word is heard here either, as if dealing with language were impossible in the context of their appearances”, and continued:“people are robbed of their language, their social competence and interaction, precisely because no communicative or social exchange is possible in this system.” Giving language back its communication potential and physicality by means of performances or through work in public, social spaces was a programmatic decision on the part of the artists. Just as art is a pre-linguistic, symbolic form of communication, it is also a form of symbolic exchange, purposeless and unconstrained, and for a century now, it has been the rule that art systematically violates all rules. In order to expand this exchange, making it not just symbolic but also real, artists seek channels other than the existing art spaces, new places where real interaction is possible. It comes as no surprise that Szuper Gallery chose a lift, a small cell within this large administrative apparatus, as the site for its installation. Following my explanations above of their playful scratching away at status symbols, the choice of a transparent cell – which is surely an allusion to both the new democratic political culture and modernist clarity – should be read as highly symbolic. It is part of a larger structure, and it can be used individually as well. It behaves autonomously, if you want to call it that, and one can remain in this cell and allow a choreography of everyday life in the administration building to evolve.The ascending and descending are ensured by pre-programming. The “archive” functions like an institution parallel to that of the office of the local administration, and it seeks to develop a parallel narrative of the place. Thus it has both symbolic value and use value. structure, form and content are all easy to grasp. The archive offers entertainment and distraction for visitors while they wait. As the artists wrote in their description of the project, it also offers an opportunity to grapple with various aspects and questions of the personal meaning of public space. Szuper Gallery thus looks for a place of possible exchange, but it does not set up a clear partition wall between the institutional and the individual, artistic territory. In the Liftarchiv, Szuper Gallery offers a new functional possibility; it is, however, only a potential offer, a possibility made freely available. The choice of the local administration office as a site is particularly symbolic, because, as Heinz Schütz writes in the catalogue:“As a public manifestation, art in a public space is subject to the provisions of public order; at the same time, however, it is granted a kind of special status.The right of free expression, whose practice is regulated by the office of the local administration, and the freedom of art as guaranteed by law may intersect, but the two fields are by no means completely congruent.” This Liftarchiv can and should also be seen as a site of information where artists’ groups like Szuper Gallery that have been working for years in self-managed networks can organise their own presentation sites, their non-institutional “niches” inside a prestige structure and thus set up a microspace within the macro-space.These new working strategies of visibility and distribution are developed by these artists’groups alongside, together with and often outside of the institutional art world.

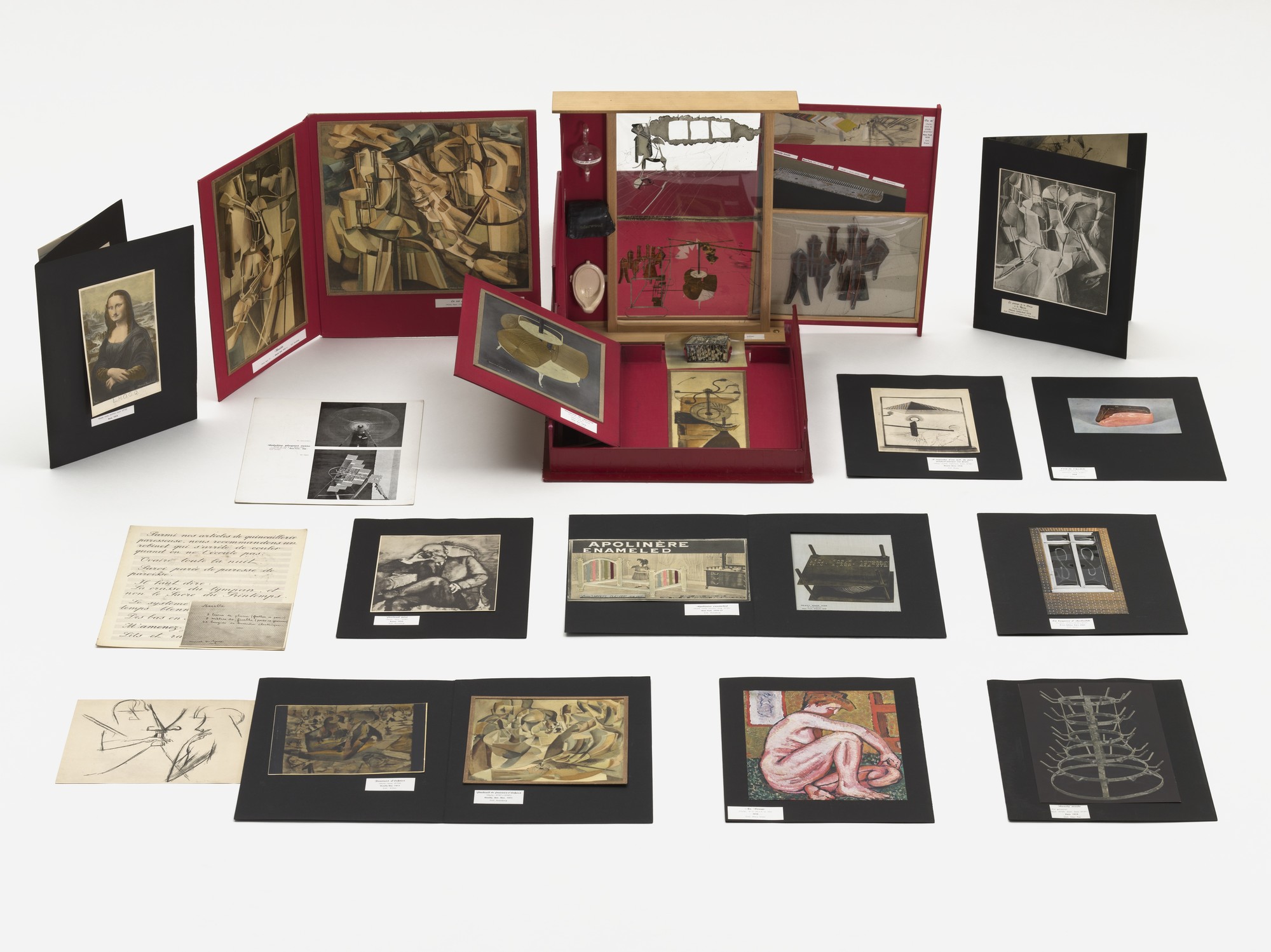

Their ephemeral manifestations are condemned to amnesia. Thus a whole spectrum of artistic production is cut out of the art historical narrative found in museums. Now, thanks to the initiative of Szuper Gallery, several of these works and practices will be accessible, as all the documentations and information are being made available in compressed form. Just as Marcel Duchamp was active for many years as an artist before he came up with the idea of collecting his work, which until then had been ignore, in the archive of his Boite-en-valise (Box in Valise) around 1936 to 1941. The liftarchiv should be located in a similar place in the history of art. Duchamp’s Boite-en-valise contained not only the works themselves but models of all his earlier works in a miniature format. The visual quality of the works was reinterpreted as information. They were merely references to real works: meta-signs. In that sense, the Liftarchiv contains, the Munich art commission’s “boite-en-valise”, so to speak. Perhaps Duchamp’s famous archive suitcase in precisely on of the solutions to the problem of exploding the “retinal concept of art” that Marcel Duchamp was thinking of when he went to Munich’s local administrative office in 1912 to register as a foreign artist.

This text is taken from the book Liftarchiv, ©Copyright 2007 Szuper Gallery, published by Revolver ISBN 978-3-86588-403-9

“Box In Valise” (First Image) by ©MoMA under “fair use”