At the invitation of Szuper Gallery, schleuser.net (i.e.“refugee-smuggler.net” – Trans.) made an appearance in the Liftarchiv at the local authority of the state capital Munich.The function of this government office is not simply to make available to the city’s “citizens” documents relating to administration and to manage the associated data; rather, it is also responsible for processing applications to be granted the status of citizenship and, in the process, to reject some of those applications. In this context, “citizen” refers to a status that functions as a complement to the bureaucracy.

In response to the criticism and distrust of the bureaucratisation of society that has existed at least since Max Weber, this office is making efforts to gain acceptance by its customers: the citizens. As part of this trend, which can be seen as analogous to a broader principle of customer friendliness, the city government decided a few years ago to change its architecture, introducing a bright foyer open to the outside – that is to say, at the architectonic borderline between inside and outside – as a visible expression of the citizen’s friendly reception. An artistic contribution was planned as well, and presumably the crucial factor behind that decision was the fact that these days it is generally agreed that one aspect of the proper tone of customer service is to indicate an openness to individual requests – and what could be better suited to that than art?

These efforts do not, however, apply to the other function mentioned above.There the trend to “move closer to the citizen” is counteracted with a trend to more frequent rejection of non-citizens.Talk of non-citizens’ ambitions to self-realisation, creativity or curiosity may seem outlandish in the face of a lack of elementary preconditions for individual latitude in shaping one’s own life. The range of alternatives to the role of the patient applicant (with little hope of a future) is so narrow here that it is scarcely possible to imagine any interest in art.

The commission of the city planning department that was responsible for the choice of art at this location did, however, approve, in the form of the Szuper Gallery’s Liftarchiv, a concept that pays a great deal of attention to precisely this hidden aspect of the reshaping of the relationship between bureaucracy and individual. Observing this dark side of the status of citizens thus goes hand in hand with a search for alternatives to the dominant order, which might at first seem to mean above all the search for possible forms of resistance.

It must truly be called the dark side of the status of citizen, in part because the complementary roles of citizens and the bureaucratic organisation are based less on a transparent discourse or rational consensus than on tacit recognition of relationships, and presumably that is precisely how they acquire their essential function. Whenever dissent is articulated, it cannot, conversely, be perceived as binding criticism within the horizon of general problems but must instead be assessed as a potential threat to a structure to which the society has adapted and which views itself as a normality that is cordoned off as much as possible.

Consequently, the concept proposed by schleuser.net responds to this impossibility of objective discourse by offering an aesthetic strategy for re-evaluating symbols. The installation Do We Really Need a New Anti-Imperialism? does not formulate and manifest a direct criticism against an institution (however that might be orchestrated) bur rather introduces an organisation that sets the cross-border traffic in motion at this systematic point.

Hence in this first step the members of Szuper Gallery avoid triggering the predictable “normal” defensive reactions; instead, they produce a situation that vexes these very reactions. Neither do the members of Szuper Gallery simply adopt a position contrary to this or any other social reality, nor do they merely play the victim card, which would implicitly acknowledge the organisation’s role. Instead, they themselves make a point of behaving like a customer-friendly institution that is integrated into a network of activities and is working to optimise social mobility and homeostasis – that is to say, genuine, standard demands of modern societies.

Relative to their circle of customers, they position themselves as outside the boundaries that separate citizens and their normality from the rest of the world, and they are occupied in practice and in theory with the questions raised here. Nevertheless, they employ methods that all but personify this normality inside those borders.They offer a customer-friendly service for those who want to cross borders.They study, collect and archive information and knowledge that can be used for that purpose, and they form an organisation that can bring this information to bear in the political field in the name of its (potential) members.Thus the members of schleuser.net treat those who have been excluded from the normal rights and opportunities of citizens as already, in that tacit sense, citizens who must be provided for officially.To put it another way, they offer themselves as a kind of supplement that merely extends and completes the government office’s area of responsibilities.

Naturally, this deconstructing game with a border that is at once preserved and redrawn in every social operation that refers to it does not go unnoticed. From the standpoint of an individual suffering under the bureaucracy, it is possible to appreciate this deft turn against one of the bureaucracy’s own weak spots. From the perspective of those who are concerned about the absorption of social insecurity, it is already touching sensitive spots. In this respect the members of Schleuser.net are not exactly acting cautiously; indeed, the emotive word “anti-imperialism” in their eye-catching title directly provokes the system of early warning sensors.

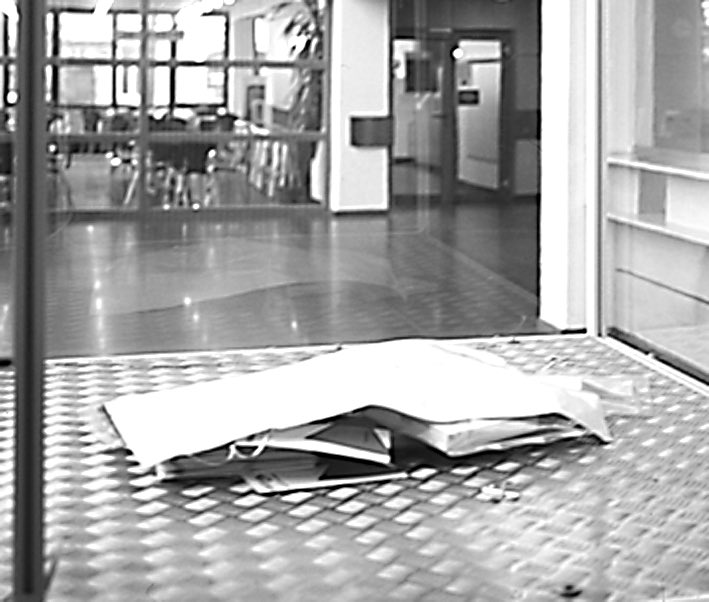

It is hardly surprising, therefore, that it would also trigger a counter-reaction in an office such as this one; if anything, it is surprising that the response was so circumspect: without saying a word, the offending text and the associated installation were covered up, and for a time no one was officially notified of that action. In all probability, it should be understood as having happened in anticipation of turbulence that result when other government offices, the press, or the artists of Liftarchiv/ schleuser.net reacted, generating a conflict that would create more waves than would be compatible with the ideal of unquestioned continuation of operations.

With respect to this more or less predictable manoeuvre, however, the artists were less concerned to insist on any particular manifestation than they were to explore real actions, sensibilities and latitudes as elements of a dynamic context in which borders not only have to be defended but also permanently reproduced. Which operations those involved carry out, or how they decide in this sort of ambiguous field of options, can only be calculated as long as the other side in each case clings to expected patterns of behaviour. In that sense, the agreement reached between Szuper Gallery, schleuser.net and the hosting government office – that the reaction was not censorship but itself an artistic action – was a surprising reinterpretation of the usual case of free artistic expression being hindered by the bureaucracy. From the perspective of art, the most interesting aspect is that it maintains the build-up of tension of a symbolic intervention that draws the viewers’ attention to the ambiguity of social processes of coming to an agreement. Particularly when one of the parties involved is an institution of seemingly unfailing solidity, this result can express in concrete terms the expectation that the final decision about the possible organisation of modern societies has yet to be taken.

This text is taken from the book Liftarchiv, ©Copyright 2007 Szuper Gallery, published by Revolver ISBN 978-3-86588-403-9